From Floral Design to Hula Hoop Contests: Fun in Early Public Housing

By Alexandra Orfirer Maher, Associate Curator

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted an economic program, collectively called the New Deal, designed to provide employment and welfare to support and raise families out of poverty. The first public housing projects came from this suite of programs, agencies, laws, and reforms.

Public housing in its early years was representative of the prevailing belief that the government was responsible for taking care of its citizens and that housing was one piece of that care. But the government did not see housing in a vacuum, and most public housing projects at this time provided other types of public goods within the housing projects. Some of these programs included schools, health clinics, vocational training, and voting drives. Public housing agencies organized a number of programs and activities aimed at providing recreation, exercise, cultural connection, and, most importantly, fun!Public housing in its early years was representative of the prevailing belief that the government was responsible for taking care of its citizens and that housing was one piece of that care. But the government did not see housing in a vacuum, and most public housing projects at this time provided other types of public goods within the housing projects. Some of these programs included schools, health clinics, vocational training, and voting drives. Public housing agencies organized a number of programs and activities aimed at providing recreation, exercise, cultural connection, and, most importantly, fun!

Let’s take a look at some of these initiatives.

Floral Design at Channel Heights Housing Project

Residents of the Channel Heights Housing Project in San Pedro, CA pose with flower arrangements at a flower show held at the housing projects. Channel Heights was a war-housing development built in 1942 that offered a store and market buildings, as well as a crafts center, nursery and school buildings, and a community meeting and recreational center. It has since been demolished.

Spaghetti Eating Contest at Aliso Village

Spaghetti eating contest put on by the Woodcraft Rangers, a Los Angeles based after-school youth recreational program, at Aliso Village in Boyle Heights, CA in the 1940s. Aliso Village was built in 1942 as part of a slum clearance project and was one of the first racially integrated housing projects in the country. The development included a baby clinic, a cooperative preschool, and a residents’ council. It was demolished in 2000, displacing two-thirds of its residents.

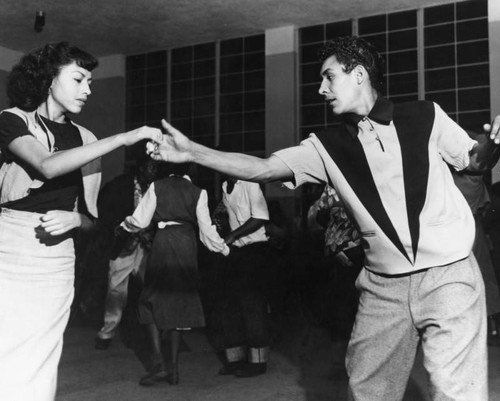

Dances at William Mead Homes Housing Project

Teenagers dance together at an event at the William Mead Homes Housing Project in Chinatown, Los Angeles, CA. William Mead Homes opened in 1942 and became a site of controversy, as it was built on an oil refinery and a hazardous waste dump. The project underwent a massive cleaning project in the early 2000s, with the Housing Authority suing ChevronTexaco for the clean-up costs. It is still operating today.

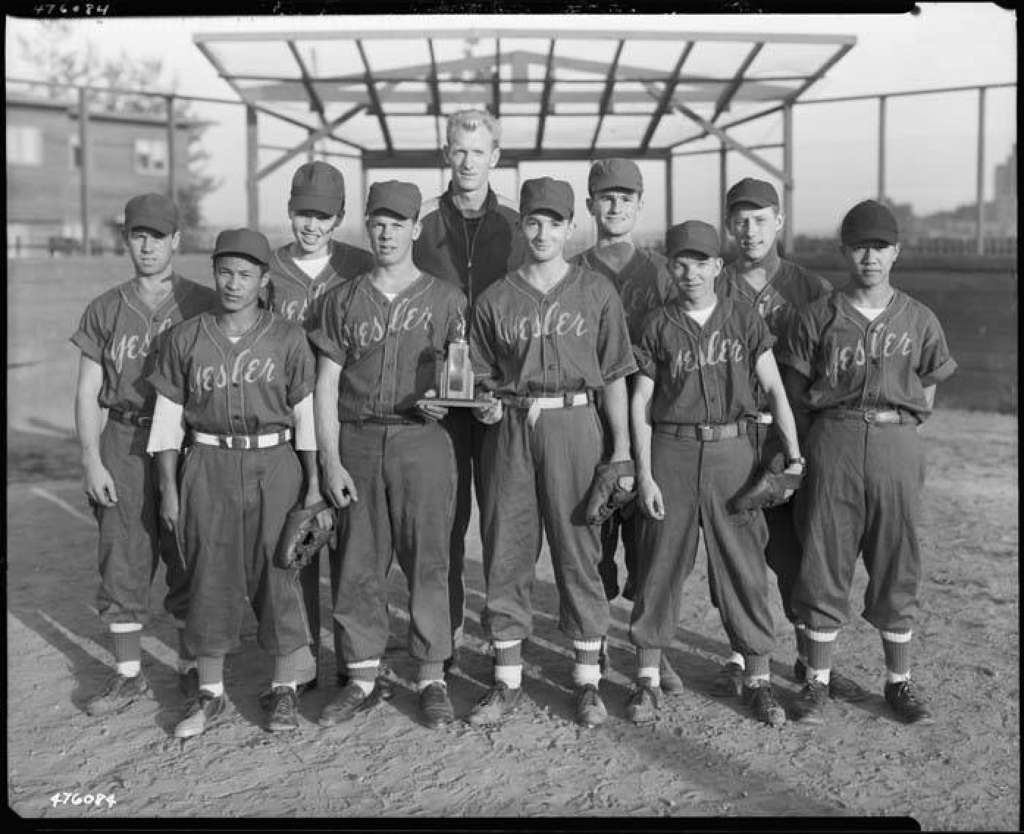

Baseball Team at Yesler Terrace

This 1947 photo shows the members of the Yesler Terrace boys’ baseball team at Yesler Playground with their coach and their trophy. In 1941, Yesler Terrace became the first public housing project completed in Seattle, WA, and was racially integrated. In 2013, Seattle began a large redevelopment project on Yesler Terrace that is still in progress.

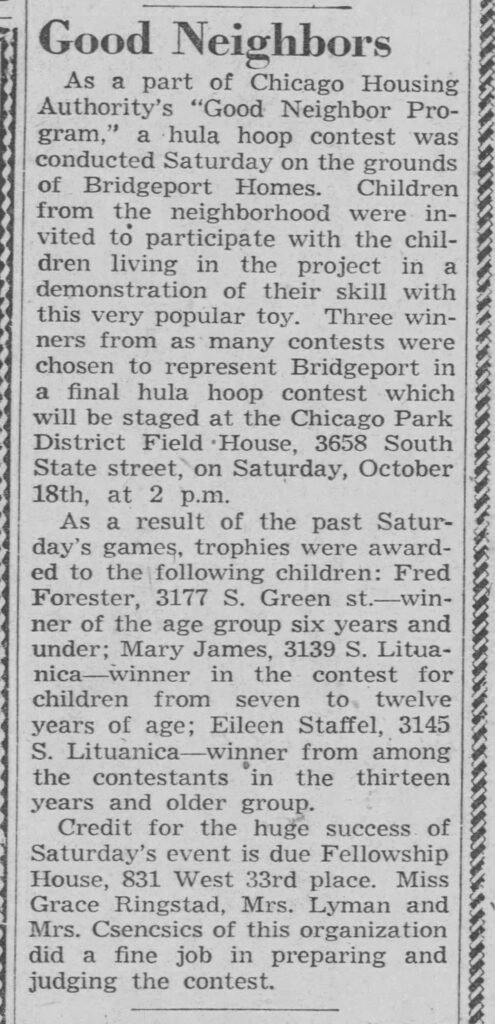

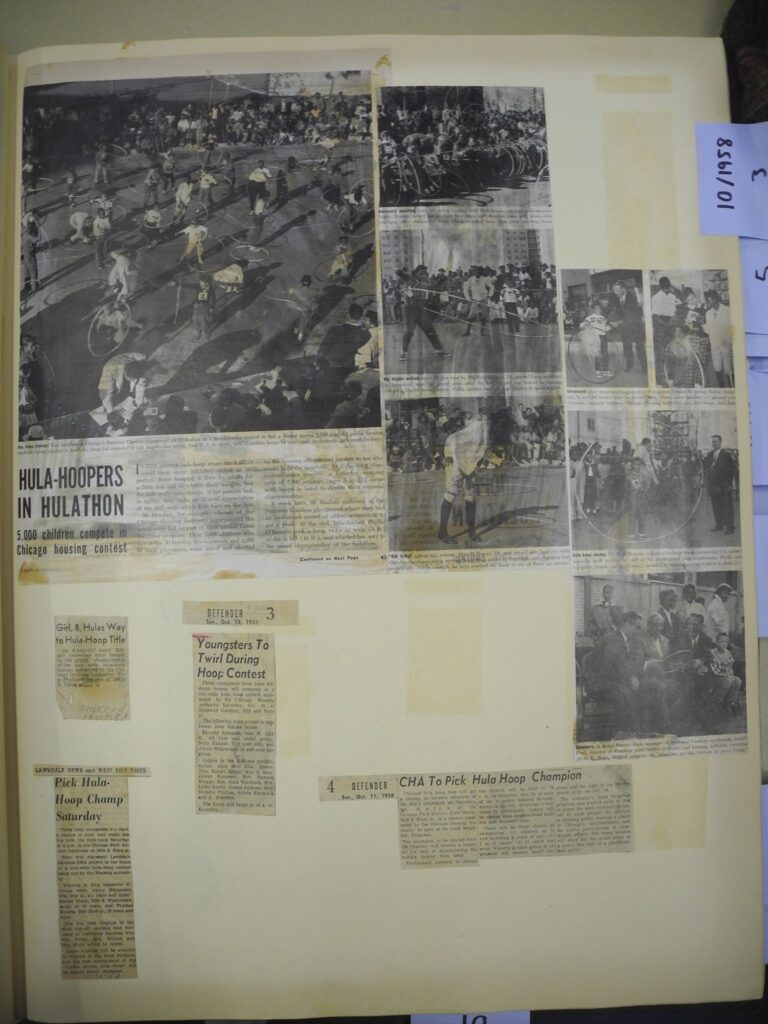

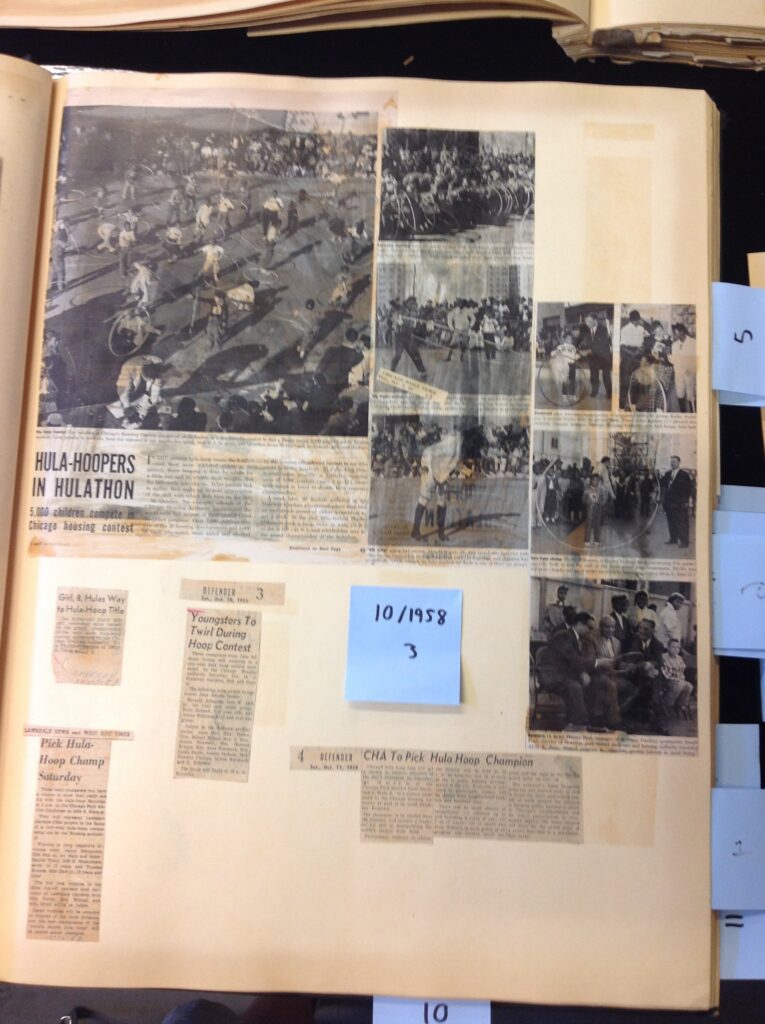

Chicago Housing Authority’s Hula Hoop Contests

In October of 1958, at the height of the “hula hoop” craze, Chicago Housing Authority staged a hula hoop contest as part of its “Good Neighbors Program.” The program was created to honor the most outstanding tenants who demonstrate public housing as a credit to Chicago’s neighborhoods and for active participation in community affairs. Winners of the various contests received prizes and the grand prize was drawn for at the CHA annual Christmas party: a year of free rent. 5,000 children from across the city’s housing projects competed in the hula hoop contest.

May Festival at Jordan Downs Housing Project

Children dance around the maypole on May 1, 1952, at the Jordan Downs Housing Project, located in the Watts section of Los Angeles. Opened originally in 1942 as a war-workers’ housing project, it was converted into general public housing in the early 1950s. Jordan Downs is currently under construction in an ongoing redevelopment project.

Advocating for Recreation in Jane Addams News

The Jane Addams News was a long-running resident-run newsletter from the Jane Addams Homes in Chicago, IL (the future home of the National Public Housing Museum). In a newsletter from 1935, the author discusses the benefits of starting a recreation program, particularly as a deterrent for juvenile delinquency. More essential, though, is their concluding argument:

“It is the belief of the writer that the real reason why we have failed to provide adequately for the recreation (play hours) of the child is that we have taken it out of the home, the school, the church, and the community setting of the child. Recreation is not a subject such as geography. Recreation is living. We do not teach children how to play. They know this well enough. We must devote our thinking to how we can help children get the most out of their play, by contributing to the growth of the child.”

Investing in Play

It is important to reflect on the ways that public housing integrated play into services, as it reminds us that various public needs are intertwined with others—and the public resources offered should be as well. Housing is not only about providing shelter but also about creating vibrant communities that foster health, safety, and connection. Supporting recreation as a fundamental part of public housing acknowledges the full humanity of residents. As our mission statement says, every person deserves not just a place to live but a place to call home.

This blog does not represent the full geographic, racial, or urban/rural diversity of public housing in the United States. This is a result of the fundamental nature of archives. Public archives, such as those at libraries and universities from which most of these photos are sourced, are primarily made up of material donated from “notable” people and other institutions. As a result, there are significant gaps in the public record, especially those about the experiences of marginalized people.

At the National Public Housing Museum, we are committed to what Black archivist Lae’l Hughes-Watkins coined as “Reparative Archiving”: filling in those gaps through efforts such as our oral history program, which gathers the stories of everyday people who live and lived in public housing. We are also interested in engaging with your private archives: your photo albums, attic boxes, and junk drawers.

If you have photos of play and recreation in public housing that you would like us to incorporate into this blog post, please reach out to [email protected].

Let the fun continue

While the focus of this post is on organized recreation by the public housing projects themselves in the first few decades of public housing, the fun doesn’t stop there.

Our oral history narrators have described hundreds of ways they played in public housing, from Phillip Ayala playing ball in the field near the ABLA Homes to Sunny Fischer falling on the asphalt while playing on the playground at the Eastchester Projects, now named Eastchester Gardens.

Tune into our Out of the Archives episode “Episode Two Redux / Bringing the Outdoors In: Community and Recreation in Public Housing” to listen to stories across the country and throughout time that demonstrate the many ways kids have had fun in public housing.

Also, take a look at our Artist as Instigator Marisa Morán Jahn’s current projects. Marisa’s artwork is inspired by the WPA-era designs integrated into public housing before the 1950s, during a time when recreation, joy, and play were valued as essential aspects of a community and home.

Marisa says, “We all deserve equal access to recreational spaces, which have been systematically underfunded in public housing since the second half of the twentieth century. As an artist, I am inviting viewers to tap into their memories about childhood wonder and play in order to help reverse this inequity.”