Play Ball: The Legacy of Sports in Public Housing

–

Kids play baseball in front of the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project in St. Louis, MO. Date unknown.

From baseball to boxing to basketball, sports have a long history in public housing. Like kids from anywhere, kids growing up in public housing made fun however they could. The excitement of being a part of a team cultivates a sense of community. Public housing sports leagues have provided a sense of safety and comfort in their spaces.

Tanisha Wright, Atlanta Dream Head Coach and former resident of Mon View HeightsAnd that was just something fun, like me and my friends would just play basketball all day every day, before school, after school.

Midnight Basketball

In the summer of 1986, in a town called Glenarden, just outside of Baltimore, town manager G. Van Standifer debuted his innovative crime prevention program: Midnight Basketball. He had noticed that during the summer, there was an uptick of crime and violence and most of it was committed by young men between the ages of 17-22 between the hours of 10 pm and 2 am. Standifer had a theory that if he could get these men into a structured activity at that time, he could reduce drug-abuse and crime. It wasn’t just basketball that he was relying on, participants in Midnight Basketball were also required to participate in enrichment programs such as drug education workshops and career counseling. They also offered partial scholarships to vocational schools.

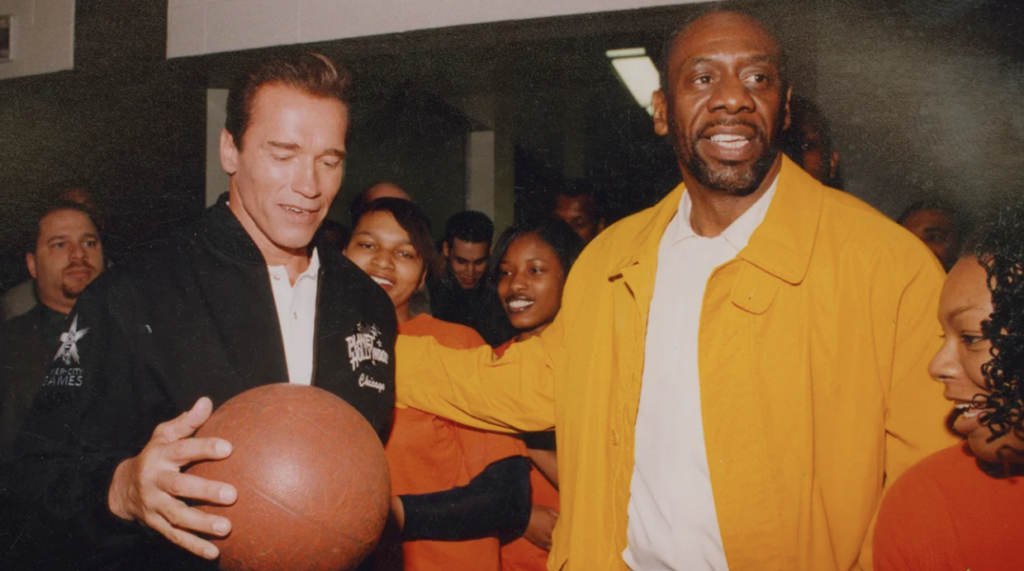

The program garnered immediate support across the political landscape and was soon copied by other cities. In 1990, Midnight Basketball came to Chicago. Inspired by the Glenarden model, Gil Walker, Director of Residential Programs at the Chicago Housing Authority, took it further–this was Michael Jordan’s Chicago, afterall. Walker wanted the young men to feel like they were really in the NBA–high quality uniforms, selective tryouts, and all the rules and regulations of the league.

People were skeptical that you could bring together residents of different public housing projects across the city and not have violence. Before each league was set up, Walker and his team held community meetings and met with gang and other community leaders to reach an agreement. Midnight Basketball would be a neutral ground. If even one fight broke out, he would shut down operations in that community.

Walker had another rule–all practices and games were tied to enrichment programs. If you missed one, you would be benched at the next game.

In the early 1990s, the program continued to spread, bolstered by the press given to Gil Walker and the Chicago Midnight Basketball League. Watch Walker teach others how to create their own league.

Sun’s Up

Despite early support across the political spectrum, when Bill Clinton championed the program as part of his 1994 Crime Bill, it became a focal point of contention by Republicans. They argued that Democrats were weak on crime and that they were spending too much on programs that supported instead of punished criminals (programs such as Midnight Basketball only made up $50 million of the original $33 billion bill). Harmful racial discourse in debates about Midnight Basketball was part of the larger, racially coded, “War on Drugs” that also framed the decline of funding for public housing. Ultimately, Midnight Basketball received a much smaller sum of funding and the league began to decline. In Chicago, this decline also coincided with the onset of demolitions of public housing projects and displacement of their communities that eventually culminated in the 2000 Plan for Transformation.

Today, the Midnight Basketball League continues in 25 cities across the country with some cities even starting women’s leagues, but there is no league in Chicago. It is remembered in Chicago for its innovation and humanizing approach to crime and violence prevention.

Play On

The legacy of sports in public housing continues to today but with less fervor and less funding than it had historically. With less traditional project-style public housing, youth are more spread out using Section 8 housing and Housing Choice Vouchers, making it difficult to build the same kind of peer communities that sports support. However, housing authorities across the country continue to use sports as means to build community and life skills for young people.

And of course, as they always have, kids in public housing today will continue to make fun and games however they can.

Let the Games Begin

Keep learning about sports in public housing through our oral history podcast and Joyce Award project, HOOPS, an imaginatively expanded permanent outdoor basketball court shared by the National Public Housing Museum and a new mixed-income housing development.

New Oral History podcast episode: play ball

Our oral history narrators have thoughtfully described the impact of sports on their experience of public housing. Tune into our Out of the Archives episode “Play Ball: Sports and Athletics in Public Housing” to listen to stories of sports and public housing. Listen now!

Marisa Morán Jahn’s HOOPS Project & Joyce Award

Our recent $75,000 award, in partnership with artist Marisa Morán Jahn, from The Joyce Foundation, will support the creation of an imaginatively expanded permanent outdoor basketball court shared by the National Public Housing Museum and a new mixed-income housing development. HOOPS will preserve and promote the rich history of basketball and other forms of recreation in public housing communities. Learn more!

This blog does not represent the full geographic, racial, or urban/rural diversity of public housing in the United States. This is a result of the fundamental nature of archives. Public archives, such as those at libraries and universities from which most of these photos are sourced, are primarily made up of material donated by “notable” people and other institutions. As a result, there are significant gaps in the public record, especially those about the experiences of marginalized people.

At the National Public Housing Museum, we are committed to what Black archivist Lae’l Hughes-Watkins coined as “Reparative Archiving”: filling in those gaps through efforts such as our oral history program, which gathers the stories of everyday people who live and lived in public housing. We are also interested in engaging with your private archives: your photo albums, attic boxes, and junk drawers.

If you have photos of sports in public housing that you would like us to incorporate into this blog post, please reach out to i[email protected].