Werkz in the Archive

Taking Play Seriously

written and edited by Dr. ShaDawn “Boobie” Battle, jellystone robinson, and Liú m.z.h. chen

Want to see these films and be in discussion with these artists and archivists? Join us at Werkz in the Archive: Film Screening and Dance Cypher on February 19, 2026.

In the spring of 2024, Dr. ShaDawn “Boobie” Battle was selected as the National Public Housing Museum’s latest Artist as Instigator. She came in hot with bold ideas and spirited about collaboration. She spearheaded the project Place, Space, Werkz, an innovative mixture of workshops and Footwork cyphers that troubled four different historical violations of Black homeplace, a term coined by the late bell hooks to describe the intimate and domestic spaces of survival that Black women have cultivated for Black people outside of racism, homophobia, capitalism, and patriarchy,1 in Chicago. These violations are: No-Knock Warrants, Environmental Racism in Altgeld Gardens, Land Sale Contracts in Englewood, and the Plan for Transformation that led to the demolition of over 25,000 units of high-rise public housing structures, including the Robert Taylor Homes, the Harold Ickes Homes, and the Ida B. Wells Homes.

ShaDawn located the genesis of such violence within the dwellings of enslaved people during the era of slave patrols and the Fugitive Slave Acts.

Slave Patrol: The Birth of Modern Policing

An excerpt from Place, Space, Werkz Production

ShaDawn’s residency culminated in a Chicago Footwork showcase, where young people used the dance to tell the stories of struggles against these violation of Black homeplace. The showcase is still available to see today and will soon be accompanied by a short film about its creation process.

Following this work, in 2025 the National Public Housing Museum was given the opportunity to expand our collaboration with Dr. ShaDawn as a host site for Sixty Inches from Center’s Chicago Archives + Artists Project, exploring the following questions:

- What do artists and archivists have to glean from each other’s philosophy, training, and creative process?

- What role do artists have to play in taking action to preserve their communities’ histories?

- How do archives shape artistic futures?

Building on Place, Space, Werkz, Dr. ShaDawn spent some time with our Oral History Manager Liú m.z.h. chen, and Assistant Curator and Registrar, jellystone robinson. Dr. ShaDawn listened to oral histories in the museum’s archive about Play2 and recreation, and then conducted interviews of her own, focusing on cultural production that came out of Chicago public housing.

We were not given the responsibility of producing a deliverable during this collaboration, instead given the open, inclusive opportunity to Play together (which, for 2 Libras and a Cancer, meant a lot of intellectual gabbing on zoom). This Play space yielded a world of ideas and reflections about the concept of Play itself, including its relationship to archival work.

Today, we’d like to open that space up to our audience by sharing the central question that kept surfacing for us throughout this collaboration: what happens when we take Play seriously? When we don’t think of Play as just a way to experience joy and levity (though these are vital functions themselves), but also as an arena of moving through grief, trauma, and other heightened somatic experiences; problem-solving; and finding alternatives to dominant cultural norms?

We hope that the following vignettes, using Footwork to unpack our central question, will empower you to think more critically about how you spend your free time, how you Play, and how that pleasure might ground and sustain the very real work that we are each on this planet to do.

Footwork as vernacular language of the body

Play as Resistance

Thoughts from Dr. ShaDawn

I began writing about Chicago Footwork as an embodied language of resistance that continually asserts the humanity of Black youth in the city after several interviews in which the narrators themselves describe Chicago Footwork as a language of the body that allowed them to speak back to State power. After being physically accosted by a police officer in downtown Chicago during the height of the 2020 riots that followed the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery, one Footworker decided to respond by ascending a police car and Footworking on top of its hood. If we take this example of Play seriously, we realize it was the dancer’s way of speaking back to the State through the embodied cultural practice of Chicago Footwork.

Chicago Footwork, the vernacular dance of resistance born out of Chicago, also evidences the embodied practice of Black Play. Because it was born and cultivated in our dark alleys, dank skating rinks, and dim basements, before its global celebration and, unfortunately, appropriation, by non-Black youth outside of Chicago, it was not an art form that “the city” collectively (Chicago) heralded, or even took seriously. It wasn’t and still isn’t a dance form you’ll learn at Julliard. And it doesn’t help that it is performed by Black youth in the inner city of Chicago considered to be menaces and derelicts (or shall I say, “YNs”). Even my own mom told me I needed to stop Footworking during my summers and work full time when I was on the cusp of adulthood. However, when I returned to the Chicago Footwork culture in my 30s, I realized that Chicago Footwork has always been a language of the body—a way to speak the unspeakable. Chicago Footwork is also a vehicle through which to liberate our confined bodies in one of the most segregated cities in the nation.

The idea of Play for Black people has held various meanings across history and contexts. Play has historically referred to song, dance, wisecracking, game-playing, and other forms of merrymaking. Think Negro Spirituals. Think patting juba. Think “yo mama so fat” jokes. Think somersaults onto dingy mattresses in project playgrounds.

Today, Play remains as our recourse and embodied redress in desperate times.

Consider the viral February 2020 video of the Black woman, Johnniqua Charles, who began chanting “You about to lose yo’ job,” as she was detained by a security guard outside of an evening establishment. Her chant became a 2020 protest anthem, but it was the natural proclivity to resort to Play while in handcuffs, as a Black woman in a carceral state with a ravaging appetite for bodies like hers, that I am calling attention to. We don’t make light of unjust treatment out of ignorance or naiveté. Rather, rhythmic aurality and the movement of our bodies are rhetorical rejoinders to injustice and our means of documenting anti-Black State violence. Charles’s experience may have ended favorably for her. But Charles understood that she was being detained during a historical moment when Black people were publicly demanding accountability from repressive powers known to routinely snuff out Black life for sport. Play was Charles’s method of joining that discourse. The same can be said about Black people’s cultural responses (songs, visual aesthetics, sartorial representations, etc.,) to the August 2023 Alabama Boat Brawl, now lauded as a proud moment of Black collective resistance to white supremacy.

What we have also done as a people, across time and geography, is appropriate the political utility of Play, so that it serves our social, economic, and political interests. Semantically, it’s interesting for us to conceive of Chicago Footwork as an example of Black Play, given the intensive laboring of the body. Our bodies are “werkin!” But in interviews that I conducted for my film on Chicago Footwork, practitioners in Chicago feel a deep sense of release, levity, and freedom when their bodies move through space at 160 Beats Per Minute. We are communing with ancestors, releasing muscular tensions, storytelling, documenting our material lives, and speaking back to the powers that be. When we don’t take Play seriously, we overlook the resilience and genius of Black people. We must learn to listen differently and watch more discerningly.

When we don’t take Play seriously, we overlook the resilience and genius of Black people. We must learn to listen differently and watch more discerningly.

Playing in the Archives: a Critical Resistance

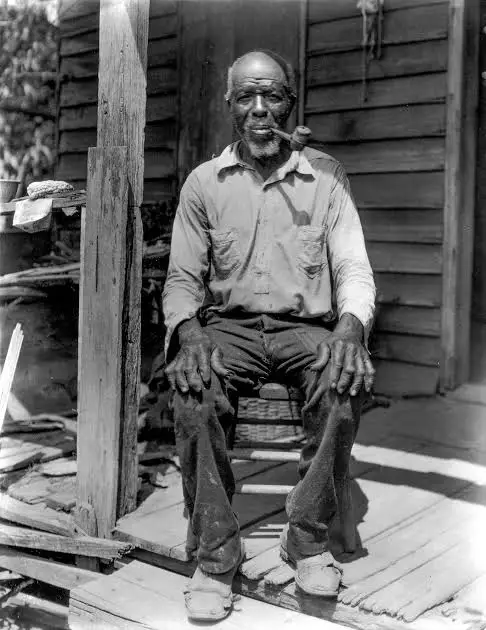

When looking at definitions of Play, we also found antonyms of Play, one of which being the word “slave.” After being captured from what is now Benin and surviving the trek through the African hinterlands, Cudjoe Lewis, born Oluale Kossola—the last known surviving African of the last U.S. enslavement ship, the Clotilda—recalled his time in the barracoons through oral history to the novelist and anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston.3

The barracoons were the slave pens erected to house the captive Africans before warehousing them on the slaver ships that lined the edges of the Atlantic Sea. Kossola was held with other young people of his nation, and so innocence protected him and the others from an immediate asphyxiating fear of the hell that awaited them. But they soon realized they were all “lonesome for [their] home.”4 They had also just witnessed the bloody massacre of their village at the hands of the Dahomey. Still, they would Play games and climb the walls of the barracoon structures to view the ships in the sea.5 This memory, relayed to Hurston, reveals how Black people resorted to Play during unspeakable cruelties. If we take Play seriously here, we know that these young Benin captives were merely trying to survive. And, in Playing in the midst of the cruel natal severing to which they were subjected, they were exercising autonomy over their bodies, using minds that could not be confiscated. They were community-building and resisting through Play, inside of barracoons. Imagine that.

Over a century later, public housing residents also Played as a way to resist structural violence. In an oral history interview, DJ Clent discusses how the material structures of racial segregation—the cinderblock walls—revolutionized the sound of Ghetto House music, electrifying the project parties in the 90s. In other words, inventive cultural production born from structural violence.

This interview with DJ Clent and his son DJ Corey was conducted by ShaDawn.

Criminalizing Play

Now translate this scene to the context of public housing. What happened to the memories and the stories tucked neatly between the cinderblock walls of the CHA Chicago high rises when they were reduced to ashes by wrecking balls and explosives?

Think of the Ghetto House parties with DJs perched atop the high rise structures, scratching and Playing revolutionized Ghetto House sounds, only made possible on account of the Playful transposing of sonic elements when they ricocheted against the cinder block walls of The Wells. The stories of gyrating bodies to DJ Slugo’s “Where the Rats,” the culture-making, the community-building—all lost when the structures were demolished.

DJ Slugo recounting words from a police officer shutting down a party in Stateway GardensIf you turn the music back on, you going to jail.

Ghetto House DJ, DJ Slugo, speaks about the parties in the projects.

This 2025 interview with DJ Slugo, conducted by ShaDawn, took place in the REC Room at the National Public Housing Museum.

What does resistance look liken when Play is criminalized?

And when the structures are gone, and nothing tangible is left, what can we use to preserve and nurture our memories that they once held?

Who’s laughter lives on when you laugh?

Who’s story gets told when you move your feet?

Could one solution lie in embodying the archive? In creating a new archive from movement and Play?

In many ways, Play has existed as a preeminent knowledge producing practice of Black culture. As Black Atlantic scholar Paul Gilroy has noted, Black people in the West have developed a knowledge of the atrocities they have suffered, understood to be “unsayable claims to truth.”6

In other words, what does it look like when knowledge of our experiences cannot be articulated through conventional modes of expression? Is there something beyond the spoken and written language—“the merely linguistic, textual, and discursive”—whether intelligible or not, that we can harness to give voice to our lived realities?7

The Black musical tradition, across history, is one example.

Drill music is abrasive, uber-violent, and for many, incomprehensible. However, it is rhythmic storytelling about growing up amidst structurally engineered violence in Chicago. It constitutes a communal exercise of survival for the Black kids in the hood—that is, Play. Drill rapper G Herbo rapped in the introduction to his PTSD album, “Real menaces, we grew up like Dennises, huh? / Played with pistols, we ain’t have no Sega Genesis, uh-uh / No curriculum, can’t punctuate our sentences or nothin’.” Complicating the fact that traditional forms of Play for poor Black kids in Chicago were out of reach was the school system that required a mastery of the “King’s English” in written form, often invalidating the credibility of their own ways of communicating. Thus, they resorted to Playing in the streets. In this video clip from G-Herbo’s piece, the young people walk nearby Wendell Phillips High School, which once housed Wells Prep, an elementary school that served mostly young people from the Ida B. Wells projects.

G Herbo, PTSD

Machine Entertainment Group/Epic Records, 2020.

One can assume that G-Herbo is both recalling a memory of his time as a young person and, by setting the music video in his own neighborhood, providing an example for Chicago Youth of how to take agency over their narratives. Drill Music is both a form of Play and an opportunity to communicate their material realities on their terms.

If we can’t understand their critiques of the disparate outcomes of differential privilege on account of race, then perhaps we need to re-adjust how we listen. Perhaps we need to take Play more seriously.

The importance of Play and taking Play seriously resonates even more deeply when considering certain limitations within the field of archives and memory work.

Archivally, records and documentation of Play—cultural production such as music, dance, film, visual art, multi-media art, and more—fill in significant gaps that plague formal archives because of the limits of what protections any archive can offer to its participants/donors. As painfully established in the infamous 2000–2006 oral history-based Belfast Project, also known as The Boston College Tapes, there is no such thing as academic privilege or archival privilege that protects information disclosed during any type of research—in contrast to how confidentiality is protected in the realms of medical care and legal counsel.

Oral historians and archivists take precautions to protect their narrators from the emotional and potentially legal ramifications of what activities and perspectives they describe in their interview(s)—steps like pseudonyms and delaying the release of interview materials until after a narrator’s death. However, if an interview is suspected to include admittance to criminalized behavior, it can be subpoenaed by the government. In the case of the Belfast Project, Northern Ireland invoked a treaty between the U.S. and the U.K. to compel a 2011 subpoena. Project managers Ed Moloney and Anthony McIntyre filed a counter lawsuit, arguing that it placed project participants at risk and would set a stifling precedent for other academic research projects. However, the courts ruled that criminal investigations take precedence over academic study. “The choice to investigate criminal activity belongs to the government and is not subject to veto by academic researchers,” it wrote. Moloney and McIntyre’s concerns about the precedent were valid—this case study is raised in nearly every conversation about oral history and the law. And it stands as a chilling precautionary tale, discouraging research that seeks to understand histories that include criminalized behavior.

This means that if an artist like G Herbo had shared his story with the museum as an oral history, we could not protect those oral histories from being subpoenaed by the government to investigate, indict, and prosecute him.

There is no such thing as academic privilege or archival privilege that protects information disclosed during any type of research, in contrast to how confidentiality is protected in the realms of medical care and legal counsel.

In the context of the National Public Housing Museum, which documents the history of a population that is already over-policed and over-surveilled, the lack of protections from the legal carceral system is all the more concerning. While our society’s understanding of criminalized behavior typically focuses on acts of violence, there are many other types of behavior that are criminalized for the sake of capitalism or power consolidation. In the context of public housing, acts such as running an informal business without a license, smoking weed, or even playing music too loud, are all criminalized. Low-income folks may find themselves needing to commit criminalized behavior for their own survival, such as stealing food, or participating in street commerce so they can pay for food to feed their families. Still others, especially those of marginalized genders and sexualities, find their physical safety threatened by domestic violence, hate crimes, or other acts of violence—and any act of self-defense can land them in the carceral apparatus. This issue is compounded by the many injustices of the criminal carceral system, including that the state has the power to decide what is criminalized—and to change those decisions at any time.

Given the plethora of injustices of our legal carceral system, archiving records of Play and cultural production are safer than oral histories in our goal to preserve marginalized histories and perspectives. However, even preserving culture has its risks: the U.S. government has used rap lyrics as supposed evidence of violent actions by many artists, including Mac Phipps, Bobby Shmurda, Young Thug, and Gunna. This is despite a unanimous 2014 ruling by the New Jersey State Supreme Court that lyrics should not be admitted into evidence of a crime.8

Play as Spiritual Practice

Play and culture have significant histories of serving as memory practices, as well as spiritual and ancestral practices. This is particularly prevalent amongst Black and Indigenous communities, along with other marginalized and surveilled communities. What happens when Play is used to protect sacred histories from those who seek to criminalize them?

Can dance tell the story when our words cannot?

While working on Chicago Archives and Artists, Dr. ShaDawn and jellystone co-produced a short Footwork film called UDK about a young person’s journey to identify himself in the present, which he does by traveling across the many layers of “home” he finds in the Footwork Circle.

This film starred one of the participants of Dr. ShaDawn’s Place, Space, Werkz Project, Fonzo, as the main character. Fonzo contributed so many creative ideas and had so many questions about how to get into filmmaking. Working with him as an actor was invigorating because he was from the places we aimed to venerate in the film. Although he had never been on a film set, the story was so much richer because of his expertise from lived experience. Although he joined as an actor and dancer, he also served as, and is credited as, a creative assistant. He’s now working on his own film telling his personal story using Footwork.

Fonzo Footworks in front of jellystone’s family house in Englewood in this clip from UDK

What happens when we take Play seriously? We resource ourselves and our collaborators with more opportunities and ways to Play.

Play, as we learn as children, is about joy, sharing, agency, and consent. It is not a trivial thing; it is not something just for kids. Play can be healing or Play can be dangerous. Play can be war or Play can be communion.

Whether we respect it or not, Play is the work. How we choose to interpret and actionize this idea may be crucial to our ability to return to a world where we can all coexist with love, responsibility and care.

Footnotes:

- bell hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (South End Press, 1990), accessible at: https://libcom.org/article/homeplace-site-resistance ↩︎

- We capitalize the word Play to emphasize it as a socio-political process of survival for marginalized people. ↩︎

- Zora Neale Hurston, ed. Deborah G. Plant, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” (HarperCollins, 2018). ↩︎

- Hurston, 54. ↩︎

- Hurston, 53. ↩︎

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Harvard University Press, 1993): 37. ↩︎

- Gilroy, 37. ↩︎

- For more about the overzealous persecution and prosecution of hip hop by the carceral system, see NPR’s podcast, Louder than a Riot: https://www.npr.org/podcasts/510357/louder-than-a-riot. See also Erik Nielson and Andrea L. Dennis’s Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America: Rap on Trial (The New Press, 2019). ↩︎